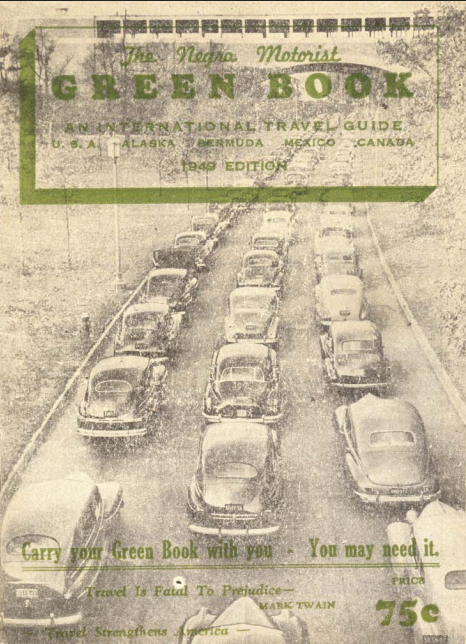

Travel during the Jim Crow era came with danger and uncertainty for African Americans. Many hotels, restaurants, and gas stations refused to serve, or would become violent toward, people of color. To help them find safe places, a man named Victor Hugo Green created a guide called the “Green Book,” becoming an essential resource for the African American community.

These pamphlets recorded specific town names with African American safe places and addresses, listing everything from taverns and inns to nightclubs, hotels, tailors, beauty parlors, barber shops, and garages. And South Brunswick has its own connection to the Green Book: The Merrill’s Road Houses and Macon’s Willow Inn, two local institutions, were listed in a 1949 edition of a Greenbook.

In 1809, Mr. Pleasant Macon established Macon’s Inn, the first African American-owned business in SB. The Inn stood at the corner of Raymond Road and Route 1, and was part of a group of restaurants and tourist homes in New Jersey nicknamed the “Big Six.” They were located in Middlesex, Mercer, and Hunterdon counties. Despite its popularity with the community, in the 1980s, the inn and adjacent service station were knocked down and have since been replaced by a Valero gas station, marking the loss of a crucial part of history for the township.

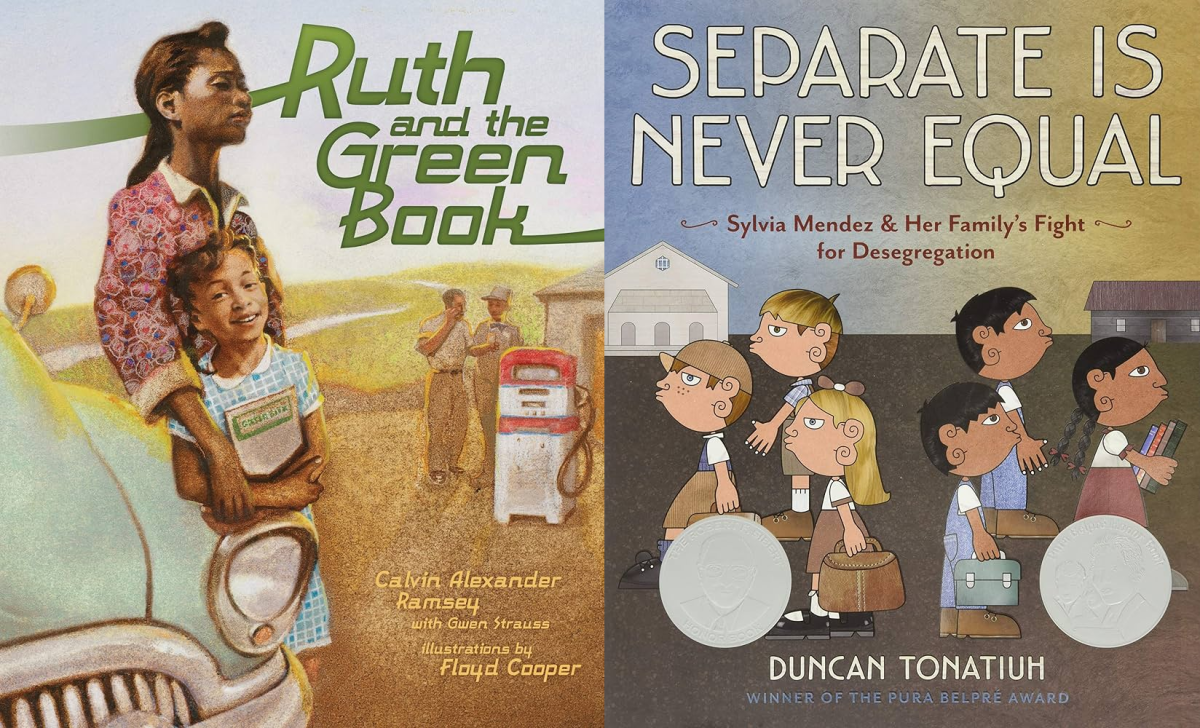

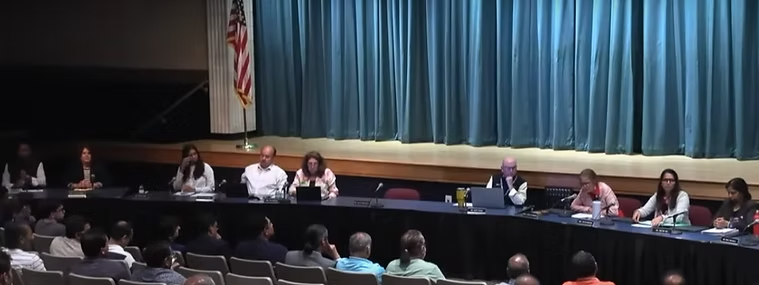

One of the books being questioned at the September 18, 2025, Board of Education meeting is Ruth and the Greenbook, by Calvin Alexander Ramsey and Gwen Strauss. It was published in 2010 and is in the SBHS curriculum to enhance the understanding of younger students about segregation in an age-appropriate way. The picture book follows a young Black girl named Ruth as she and her family travel through the South for the first time to visit her grandma during the Jim Crow era. Along the way, Ruth and her family face discrimination at gas stations, restaurants, and hotels because of the color of their skin. As they travel, Ruth and her family learn about the Green Book, a travel guide meant to help African Americans find safe places to sleep, eat, and refuel as they travel through the states during a time of racial segregation.

Dr Evelyn Mamman, the Assistant Superintendent for Curriculum and Instruction, said, “Ruth and the Green Book illuminates the reality of Jim Crow segregation and the necessity of the Negro Motorist Green Book for Black travelers. These aren’t just historical facts—they help students understand systemic racism and the courage required to challenge injustice.”

This Green Book history also inspired the Oscar-winning film Green Book, a comedy and drama film, released on September 11, 2018. Based on the true friendship between Tony Lip, a white Italian man, and Don Shirley, an African American man, it follows Tony as he takes Dr Shirley to his performances throughout the American South. Despite their differences, Tony and Don began to develop a friendship like never before, showing an interracial friendship during a time period when that was not the societal norm. While this movie is not in the SB curriculum, Green Book’s concept was inspired by the picture book about Ruth, but geared toward a PG-13 audience instead of small children.

The other book that was questioned at the September 18, 2025, Board of Education meeting was Separate Is Never Equal, by Duncan Tonatiuh. “This book is most suitable for ages 6-9,” said Dr. Mamman. She also shared that these books “are not part of the K-5 ELA or social studies curriculum now. However, elementary libraries have Separate Is Never Equal but do not have any copies of Ruth and the Green Book.”

Published in 2014, this book reinforces the themes of racism, but against Mexicans. The book tells the true story of Sylvia Mendez and her family’s fight against discrimination in 1944 Westminster, California. The main conflict of the picture book is that Sylvia and her brothers, who had brown skin and the last name Mendez, were denied entry to their local American school, while their lighter-skinned cousins with the last name Vidaurri were given enrollment forms. When Sylvia’s father, Gonzalo Mendez, tries to enroll his children in the American school, his efforts fail. The superintendent of the American school openly justifies the blatant racism, since there is still availability at the school, by claiming Mexican children needed to work on their “social behaviour and hygiene” because “they are not learning that at home.”

This conflict leads Mr. Mendez to organize the Parents’ Association of Mexican-American Children, despite warnings of “No queros problemas” (translating to “we don’t want any problems”) from other Mexican-American families in the community, who feared losing their jobs if they took action against racism. Mr. Mendez and lawyer David Marcus then filed a lawsuit, reporting that this injustice affected over five thousand children.

On February 18, 1946, Judge Paul J. McCormick ruled in favor of Mendez, declaring school segregation unconstitutional and a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment. The ruling was upheld on appeal in 1947, immediately ending segregation in those Orange County schools. Inspired by the victory, California’s Governor Earl Warren signed a law ending all state school segregation, setting a crucial legal precedent that paved the way for the national Brown versus Board of Education ruling.